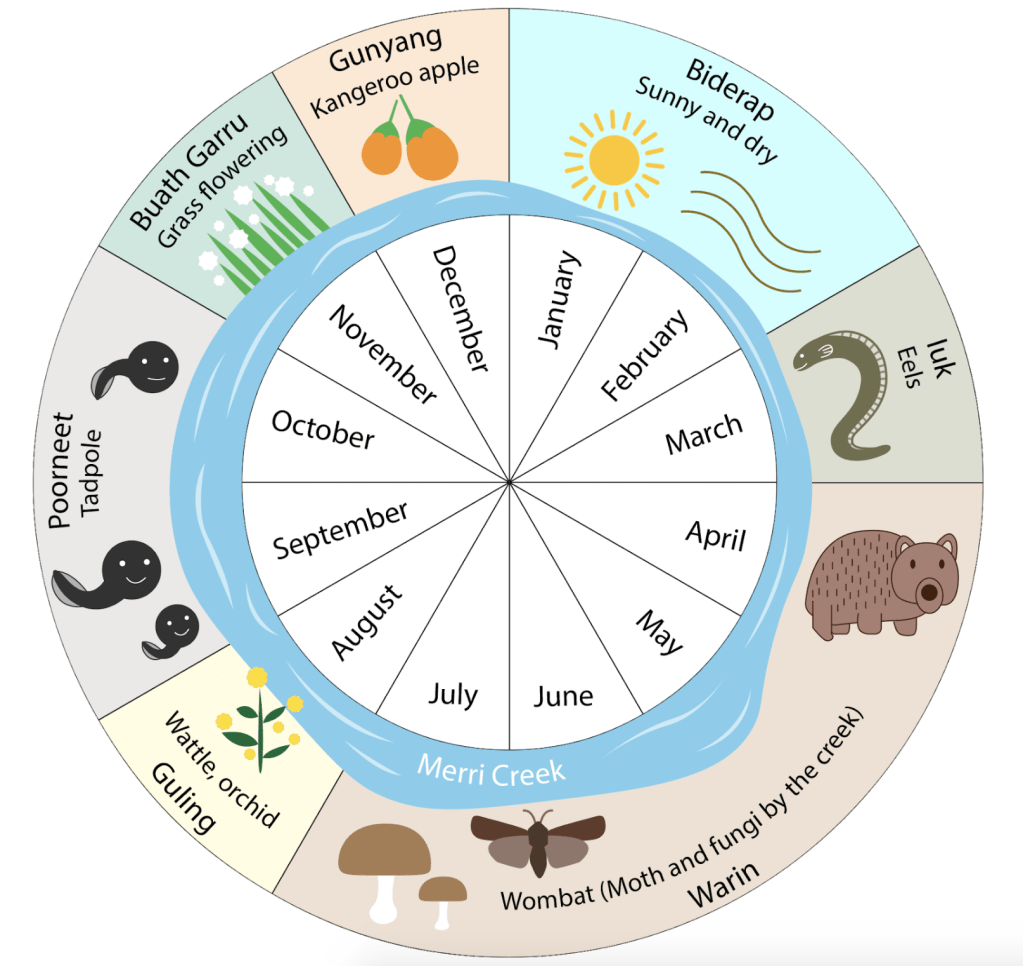

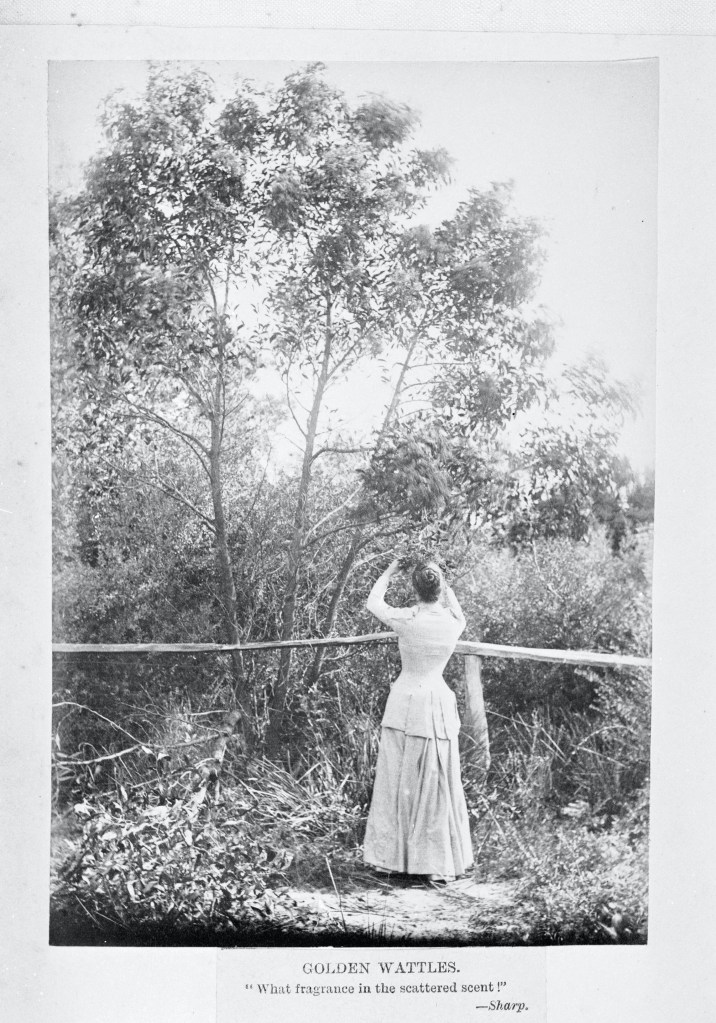

For both indigenous Australians and the Europeans that settled here the appearance of wattle in the south east of Australia has always been the harbinger of a new season. There are over 1000 varieties of the acacia that we know as wattle, and over the years they have variously provided the people living here with food, medicine, tools and weapons. In Bundjalong country, the falling of wattle blossoms into the water was a signal that the Eastern Long Necked Turtle was about to enter its breeding season, and should no longer be hunted. For the Wurrundjeri around Naam, the time of the wattle blossom is Guling season and the falling of the Silver Wattle in August was a signal to start harvesting eels. While for those Europeans of Melbourne that took to their bicycles in their thousands during the 1890s, the late August golden wattle blossom was a sure sign that the touring season is at hand.

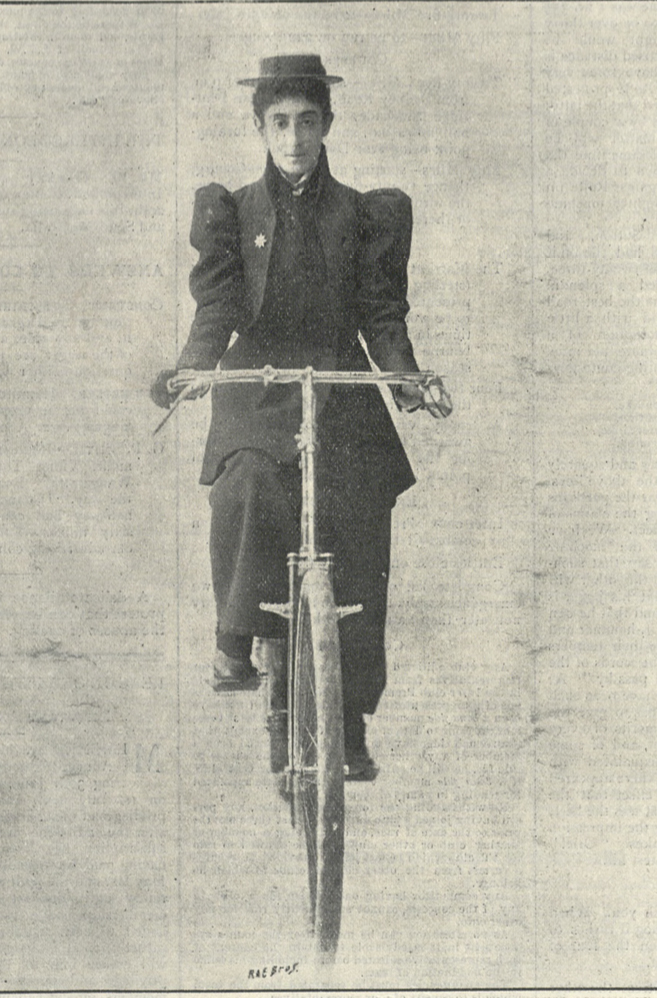

Cyclists were (and are) as seasonal as eels, for the writer of the The Ladies Column of the Williamstown Chronicle the boughs of golden wattle blossom coming in from the outlying suburbs, was all that was needed to prompt discussion on the best fabrics for summer costumes and an update on the latest fashions for that most practical of cycling costumes, rational dress.

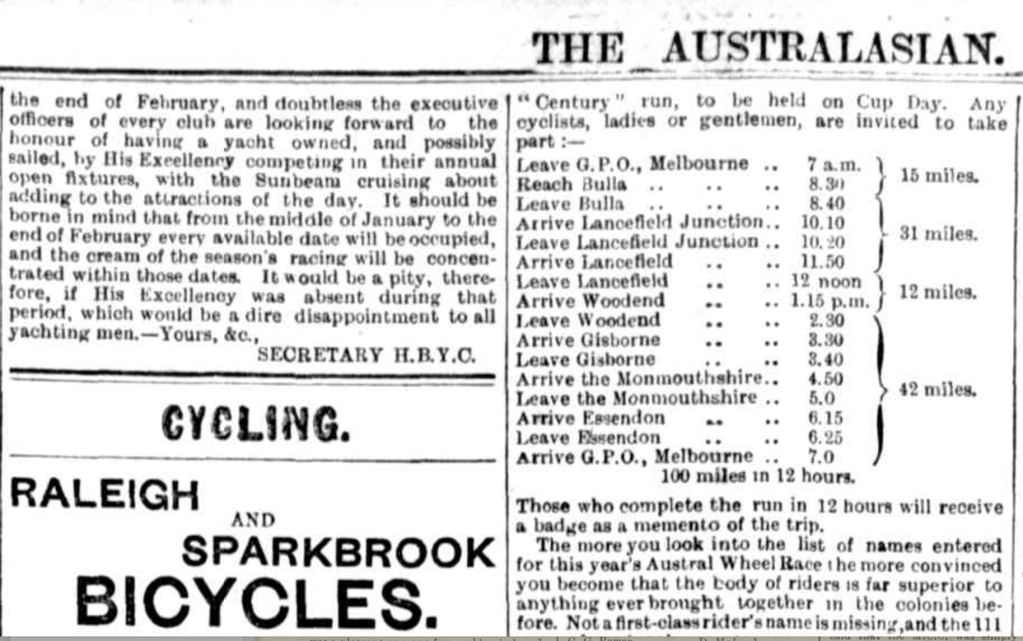

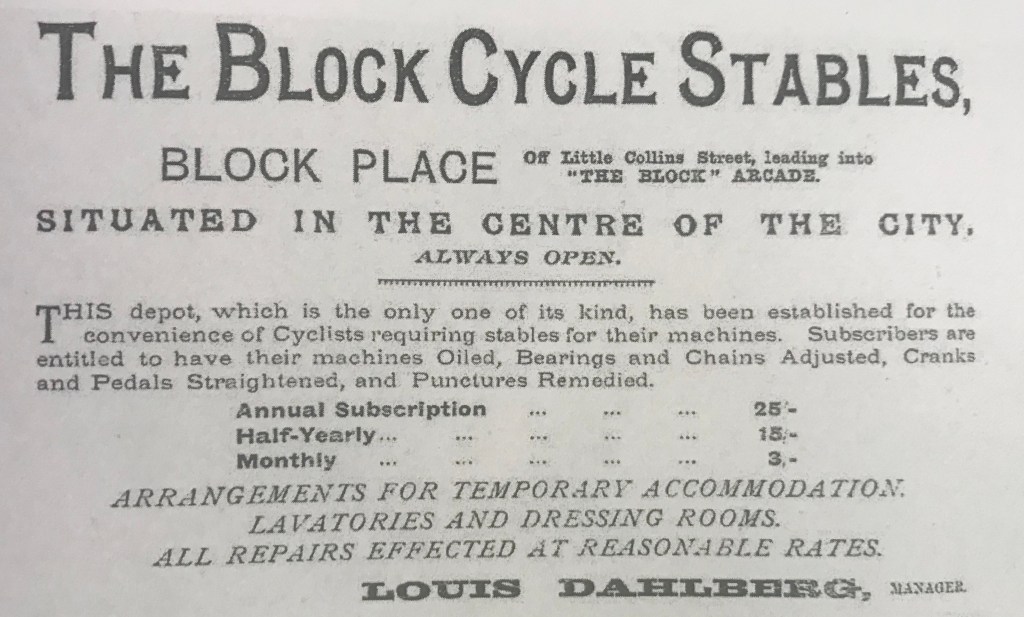

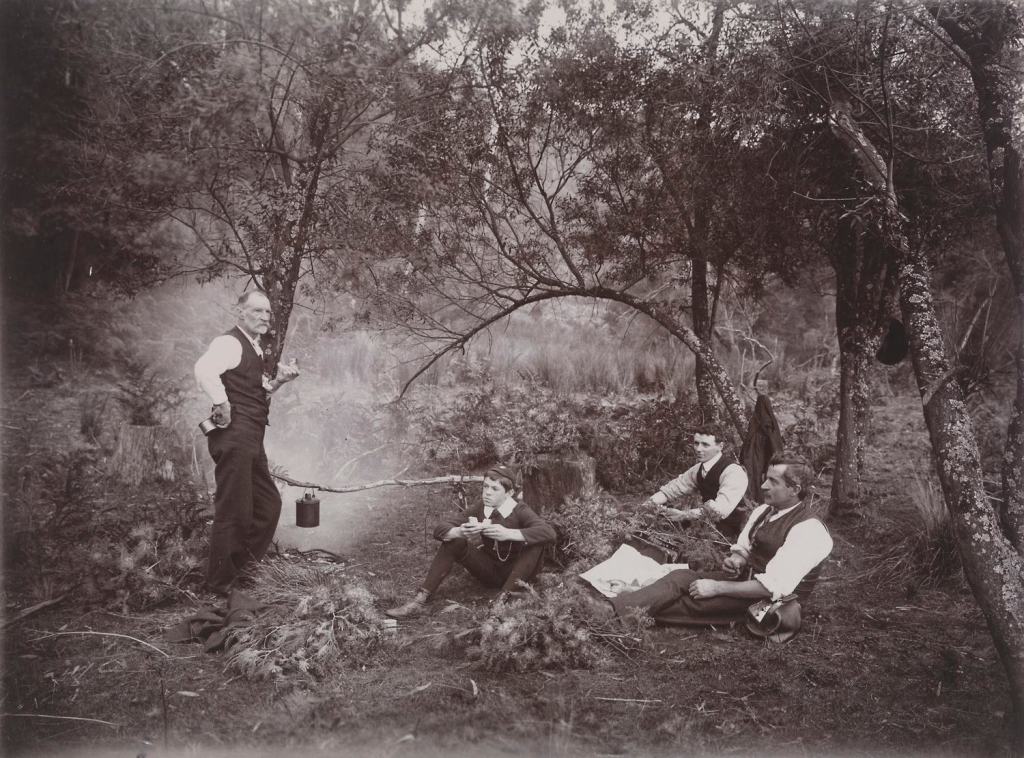

Cycling clubs diverted their regular runs to routes known for their wattle blossom and details of these routes were published for those riders not associated with a club, an increasing number from the mid 1890s. A Wattle Run, from Melbourne to Warrandyte was written up as an excellent example, and as riders headed out into the countryside reports came back detailing their finds. “At Heidelberg last Saturday afternoon the course of the Upper Yarra was marked by masses of the favourite native yellow blossom,” or “towards evening the cyclists wheeled down the hills to Diamond Creek, which place just now is a picture of blossoms-wattle and plum.” Or even further afield, To wander o’er the rugged sides of Buninyong, gathering the blue-bells, the cowslips, the dandelions, the daisies, and the perfume breathing wattle blossoms is delightful for both cyclist and cyclady.

As ever in the 1890s, no significant cultural phenomena could pass without being celebrated in song, and Melbourne Punch, the home of so many cycling journalists, published The Cyclists Song in 1895 which included the verse, “When I fly along where the wattle grows And its scent to the wind of heaven throws,”

In fact by the mid 1890s so common was the ‘wattle run’ that one columnist felt confident enough to declare: “Any man — or woman — who can ride a bicycle, and who lets August pass without a run as far as Heidelberg and Templestowe for wattle bloom has no poetry in his or her nature. Life is worth living with a good machine under one and the wattle-clad hills and gullies around.”

The wattle though, was not long destined to stay on the tree.

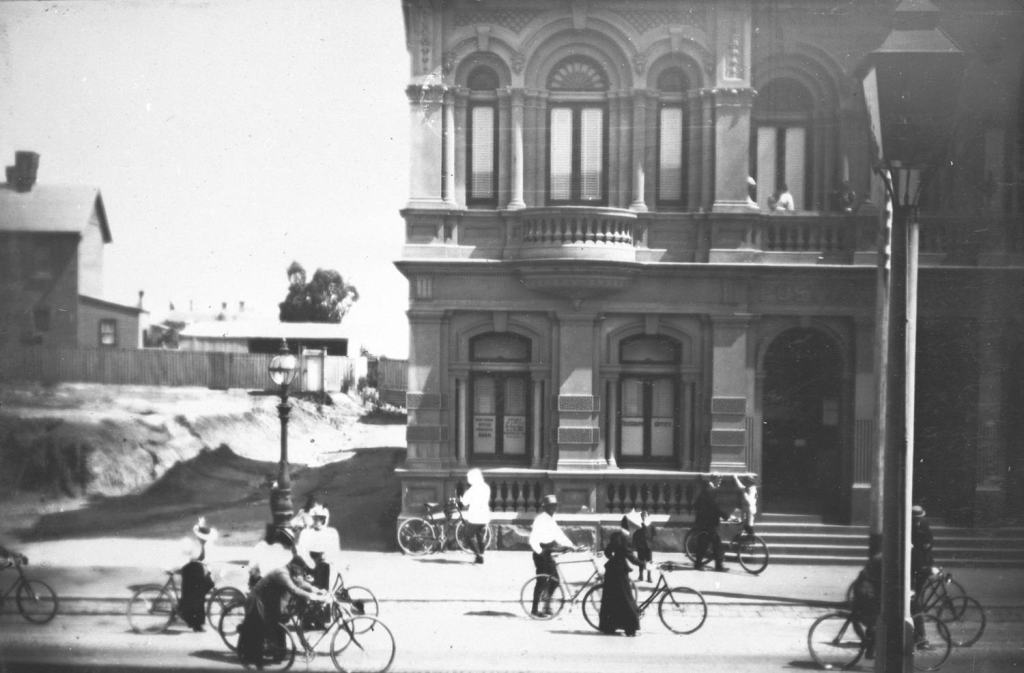

As early as the 1880s cyclists in the southern states of Australia are described returning to town after a ride, gaily bedecked in the beautiful yellow wattle blossom they had gathered. As cycling became more widespread during the 1890s, with the arrival of the new fangled safety bicycle, collecting wattle rather than just admiring it, was increasingly common. On Wednesday afternoon a number of cyclists were abroad, numbers going along the country roads and returning laden with wattle blossom reported the Geelong Advertiser one August. While admiring the quality of the wattle blossom in the spring of 1896 after a dry spell one cycling columnist noted that It is a common sight to see bicycles coming into town laden with the golden bloom. For one racing man, the sight of riders constantly coming down the road with sprays of golden wattle blossom bedecking their machines, suggesting all sorts of nice rides was enough to make him regret his choices.

But it wasn’t long before the sight of so many riders returning to the city bedecked in so much wattle started to cause disquiet. The same columnist who noted the fine quality of the wattle in the spirng of 1896 also feared that a terrible onslaught has been made on the trees this season by wheel-men.

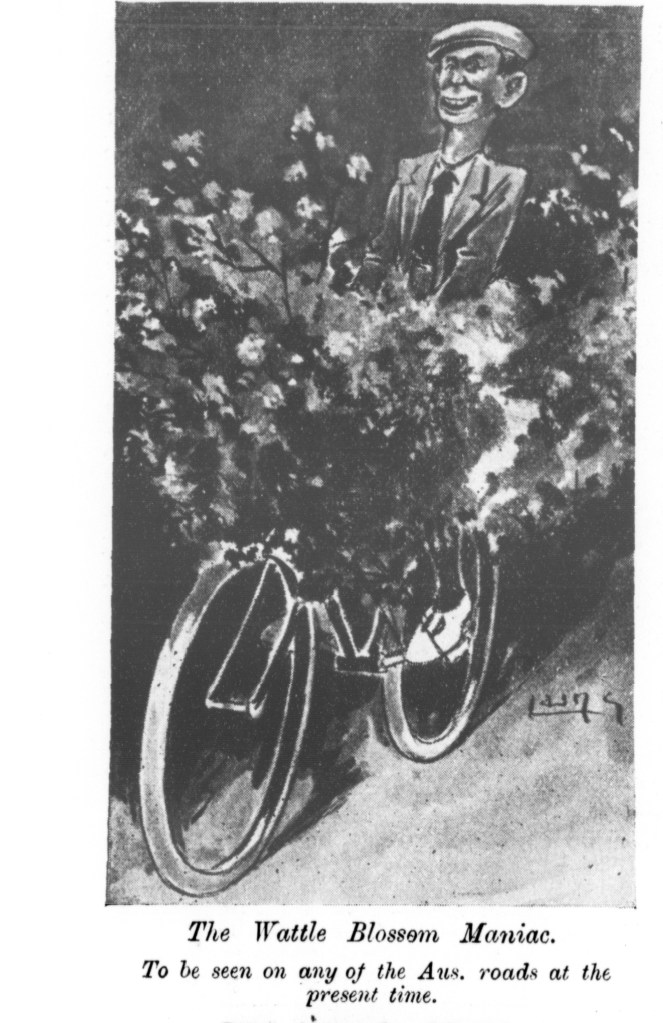

Increasingly, it was not the appreciation of the wattle being noted but it’s destruction; a race at Campbellfield saw waiting riders riding-down lanes and returning with huge masses of bloom, a lot of which was scattered about the road, ridden over, and trampled upon by hundreds of feet. As has been said, the gatherers, of blossom. do it merely for show, to draw attention to themselves, or as one man tersely put it; la colonulese,”bloomin’ skite.”

While the wattle was notorious for having inspired scores of verses of bad poetry, one letter writer to Melbourne Punch was compelled to remark that:

“Australian poets are said to find most of their inspiration, metaphors, similes, etc. from, and in, wattle-blossom. This may be monotonous, but it will not be so for long if the ruthless cyclist is allowed to have his way. On Saturday last I saw bicycle after bicycle coming in from the country each looking like a yellow cheveaux de fleurs —the rider being almost entirely hidden by wattle-blossoms. And the worst of the matter is that these vandals on wheels are not satisfied with merely taking the blossoms—they drag away branches and utterly ruin the trees.”

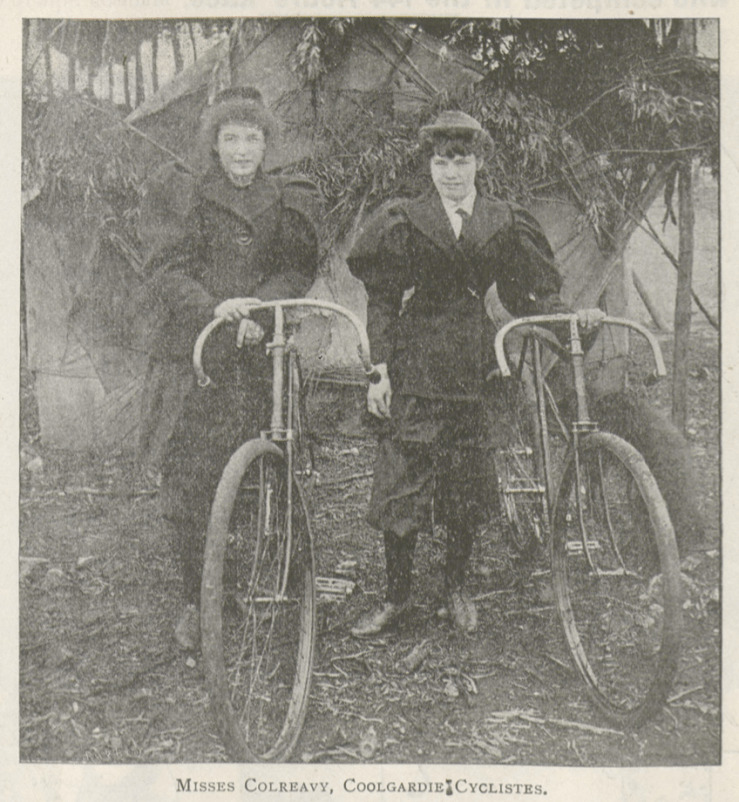

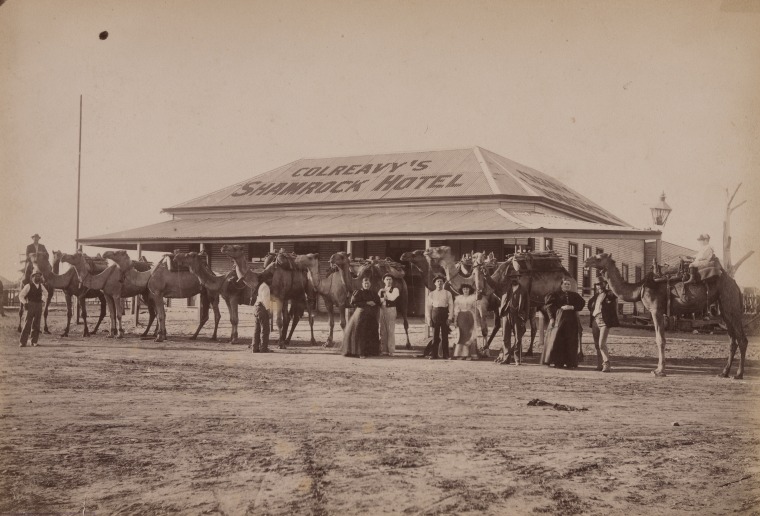

One of Melbourne’s most prominent lady cyclists bemoaned the devastation wrought to the wattle along the Yarra and made the point that “Cyclistes, (female cyclists) who are quite as fond of the blossom as the other sex, are content to take a small spray for their dresses, or attach bunch to their handle bars, but the vandals who are content with nothing less than a small tree for the vain purpose of showing off are fast becoming a destructive nuisance. Very soon we shall have no wattles on the Yarra at all, “

The Wattle Fiend as such riders became known, was even immortalised in verse, describing how They tore from off its native hedge, The golden glory of our roads. Just as the lady journalist and cyclists was keen to make the distinction between well bred cyclistes and male cyclists, this verse contains a hint that other riders were also keen to find a sub-class of riders on whom to pin the blame.The Wattle Fiend is not a ‘real’ cyclist. His ‘dusty, unwashed wheel’ a sure sign that he is one of those riders who happens to have a bicycle as opposed to those who consider themselves ‘cyclists’.

One could never have too much verse it seemed and so we find:

And the breath of spring Is heavy with the scented wattle bloom—

With the bloom, bloom, bloom. Of the sweet, sweet wattle bloom,

In Its golden glory gleaming; o’er the highways we come streaming

On our bikes, and quads and tandems, busy bent upon the doom Of the perfume-laden golden wattle bloom

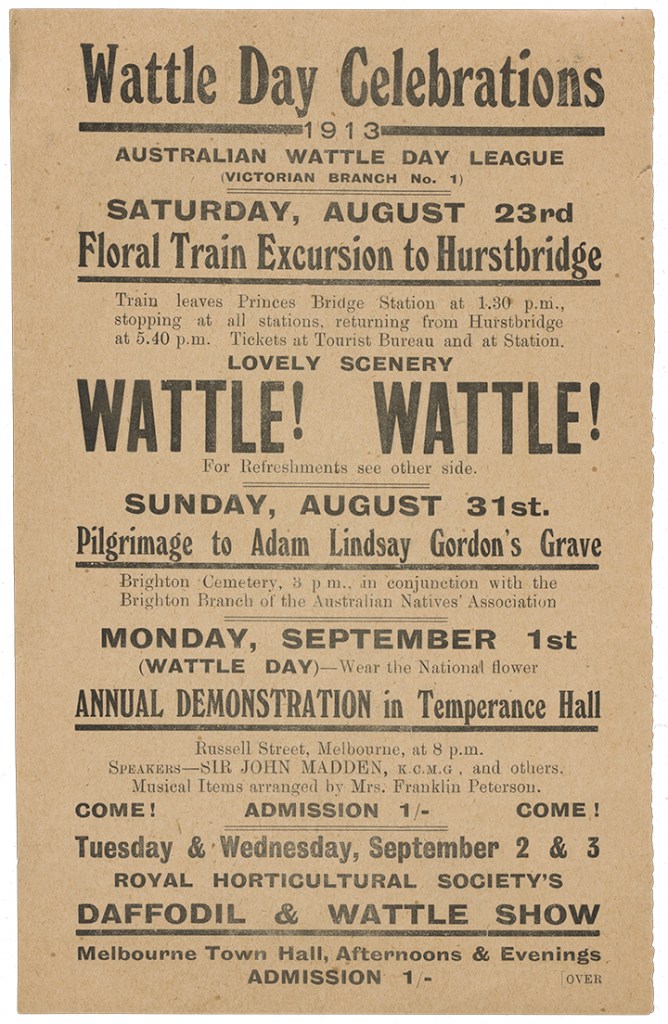

By 1898 the problem of the Wattle Fiend had caught the attention of the Field Naturalists Club, who started a campaign to protect the wattle from the ravages of riders in a series of letters to the press, a campaign that found much favour and solicited an appeal to the The Australian Natives Association from at least one correspondent. Describing how Melbourne is being robbed of its golden drapery in the most ruthless way, this correspondent went on to claim that It is one of the offences of the cyclist against society, and wheelmen are almost solely to blame.

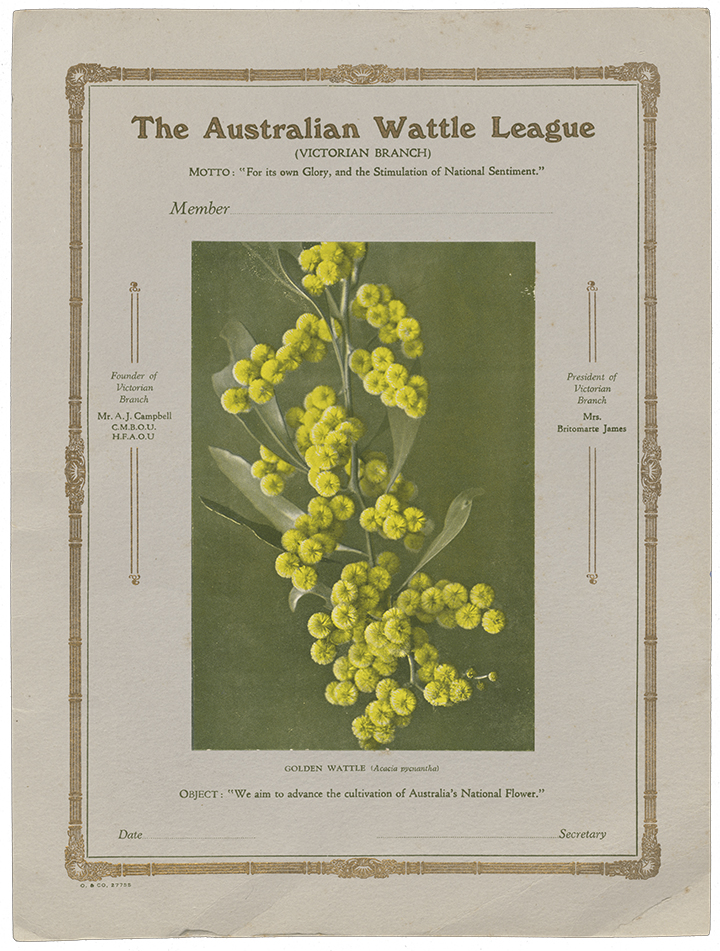

The Australian Natives Association, an organization to promote the betterment of Australian born Europeans, was quick to take up the call. The wattle had for sometime been an unofficial symbol of Australia and their women’s group had been launched as The Wattle League. Heading towards Federation, notions of national sentiment and an identity distinct from Britain ran high and the call to defend the wattle fell on primed ears.

“The Australian Natives Association is endeavouring to cultivate Australian sentiment and patriotism, and the preservation of this typical and delicately beautifule Australian flower around about the city is worthy of their attention.

The ANA were soon working in tandem with cycling clubs and imploring the League of Victorian Wheelmen to educate cyclists and impress upon them the need to not pick blossom. The League of Victorian Wheelmen took up the challenge, broadcasting amongst its members and clubs that cyclists should abstain from wanton destruction of the wattle as did the Touring Board of the Victorian Amateur Cyclists Union.

It was a move that generally met with approval, with one columnist declaring I am very glad indeed to find that an effort is being made to prevent the wholesale destruction of the beautiful wattle tree in the neighbourhood of Melbourne.

But of course, the wattle fiend had existed independently of the bicycle, and Melbourne’s wattle population had been under threat long before the cyclist took to wheel. One commentator pointed out that cyclists were the most visible culprits simply because it was quicker and easier for them to get to the districts where wattle grew.

And the reason that there was no longer wattle in the city and suburbs of Melbourne itself? Why, because it had all been picked decades before there were bicycles, of course! Other native trees like the native rose had been all but exterminated according to one writer thanks to enthusisast pickers, not on bikes.